After more than ten years, I finally returned to Japan and was able to stay a little longer than on my first visit. I was there again for a conference held at a university located in the Roppongi district, just across from Tokyo’s superb National Arts Center.

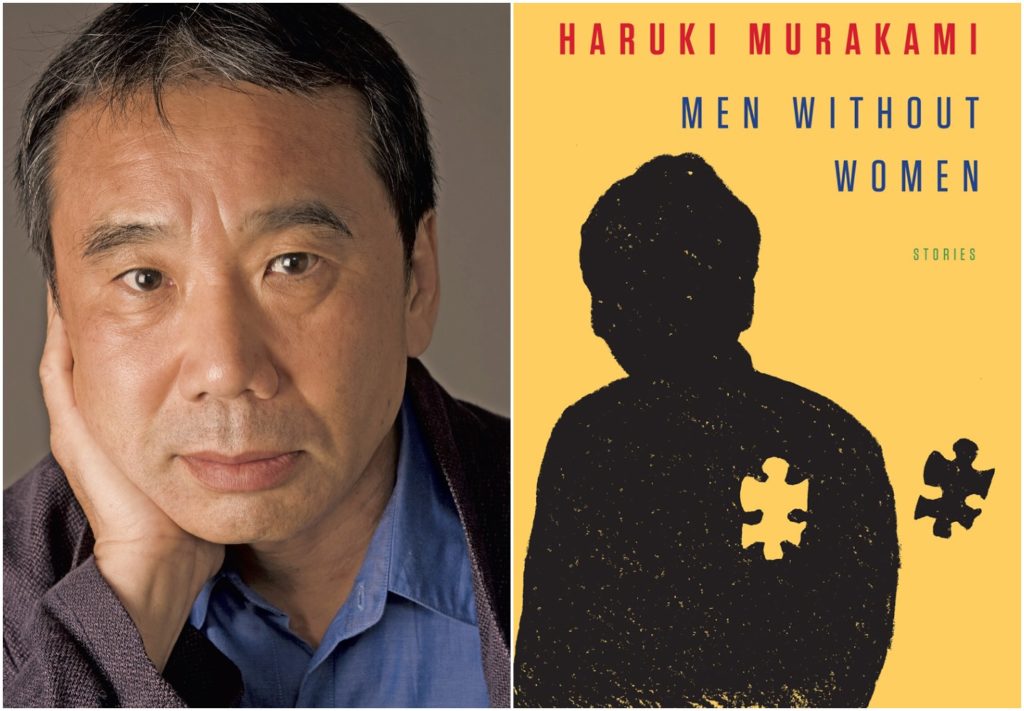

After the conference, I took the subway to another campus. Waseda University recently opened the Haruki Murakami Library (or Waseda International House of Literature), which brings together, in a beautiful architectural creation, books (first editions, multiple translations) and personal objects (including numerous vinyl LPs of the music, mainly jazz, featured in his work) donated by Japan’s most celebrated writer. I found a translation of the short story collection “Men Without Women” and chose to read “Drive My Car” on the spot. I settled into a deep egg-shaped chair and, in just under an hour, immersed myself in the world of Murakami and his story, of which I’d already seen the excellent film adaptation by Ryūsuke Hamaguchi.

Yūsuke is a theater actor who likes to drive around in his Saab 900. For insurance reasons, he can no longer take the wheel. He agrees, reluctantly at first, to be driven by a young girl, Misaki. She is a very safe driver, and he enjoys the long drives, during which he can rehearse lines from Chekov’s Uncle Vanya, the play he performs at the theater in the evenings, inserting a cassette on which his wife has recorded the lines and left blanks for his text. His wife died not long ago. They formed a close-knit couple, even if Yūsuke was not unaware that she was sometimes unfaithful to him.

Yūsuke and his driver gradually begin to talk about each other’s lives. He also tries to get closer to Takatsuki, an actor who was once his wife’s lover. Without revealing what he knows, he invites him over several evenings to talk about her.

“Drive My Car“, the title of the short story, is borrowed from a Beatles song. The same is true of “Norwegian Wood“, the title of one of the novels that launched Murakami. Toru Watanabe is a student at a university which looks like Waseda, where Murakami studied drama. It’s the late ’60s, and in Tokyo, as on Western campuses, the time is ripe for protest. The beautiful but shy Naoko, the girlfriend of Watanabe’s best friend Kizuki, likes to sing “Norwegian Wood”. They form what seems to be a balanced trio.

But then Kizuki takes his own life. The event shakes the two surviving friends, Watanabe and Naoko, but also brings them closer. They spend more and more time together, and on the evening of Naoko’s twentieth birthday, they make love. Shortly afterwards, Naoko abruptly leaves the university, writing Watanabe a letter in which she explains that she has gone to a sanatorium for treatment.

Watanabe remains at the university and meets Midori, a student in his drama class. As fragile and insecure as Naoko was, Midori is extroverted and confident. They are attracted to each other, but one day Watanabe chooses to visit Naoko at her sanatorium in the mountains near Kyoto.

This novel, nostalgic of student years, first sexual adventures and the events that determine love trajectories has been adapted for the screen by French-Vietnamese director Tran Anh Hung.

Murakami is a star of Japanese literature. During my stay in Japan, I also read the novel “Breasts and Eggs” by Mieko Kawakami, a rising star of Japanese letters. Known first for her blog and as a singer, she conducted a series of interviews with Murakami, asking him about the sexualization of women in his work.

“Breasts and Eggs” was originally a short story, which the Osaka-born author later developed into a novel. Makiko and Natsuko are two sisters, abandoned by their father and raised by their grandmother after their mother, a bar hostess, died of cancer. In the first part of the book, Makiko and her teenage daughter, Midoriko, arrive by train from Osaka to Tokyo, where her sister is trying to break into the literary world while working as a librarian. Makiko, who like her mother works in a bar, is looking for information on breast reconstruction options. Her daughter refuses to talk but is tempted by the books stacked on her aunt’s shelves.

In the second part, eight years later, Natsuko has succeeded in publishing a book, but more than her literary career, she’s worried about having a child. Since she hasn’t been in a relationship for several years, she inquires about the possibilities of sperm donation. In doing so, she comes across an association for children who don’t know their biological fathers, because they were conceived via this fertilization procedure where the donor remains anonymous.

I really enjoyed discovering, through “Breasts and Eggs”, a more feminine angle of Japanese literature, a literature which, like the country, sometimes seems to us very close in its modernity, but still manages to surprise.