Syria has been embroiled in civil war for more than ten years and has yet to emerge from it. Although fighting has subsided since 2020, the country remains divided, and Bashar al-Assad’s ironclad regime still controls most of the country. Fortunately, the presence of the Islamic State has diminished.

Since then, other conflicts have dominated the news, but every time images of war or destruction appear from Syria, it hurts. I remember the few weeks I spent there in 1993 during a trip I’ve already briefly described in a previous article. It was early spring: I remember walking along the ancient columns of Apamea as poppies covered the countryside in their brilliant red. We met people who were hospitable and interesting, even if we could feel the tension in a population held together by force. I also remember our walks along the paths that cross the gardens in Hama, following the sound of the norias that constantly plunge in and out of the waters of the Orontes.

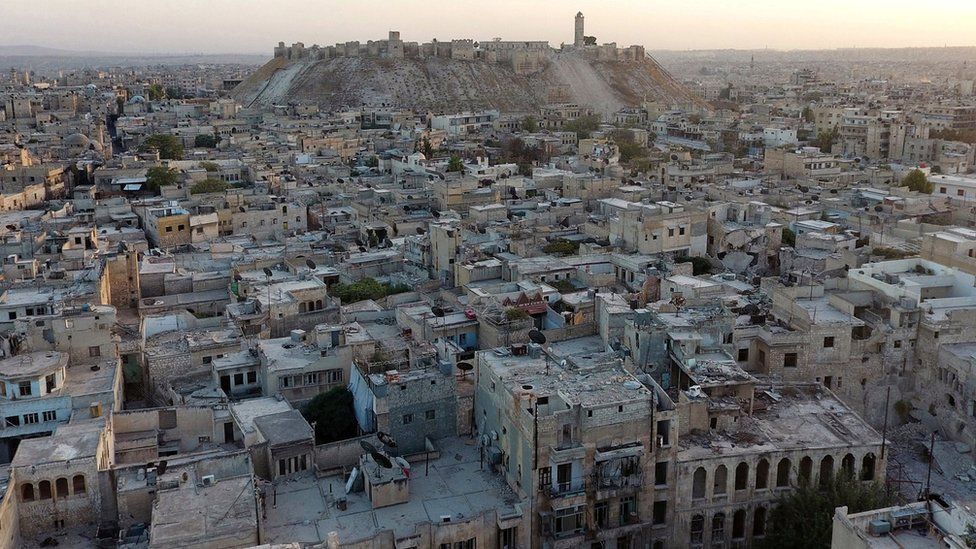

We had also spent a few days in Aleppo, exploring its bazaar, climbing to the top of the citadel overlooking the ancient city. Nearby, we visited the superb ruins of the Monastery of Saint-Simeon Stylites.

I’ve just finished reading two novels by Syrian writer Khaled Khalifa. Although they have many points in common, especially as I listened to them read by the same narrator, the two novels are very different. The first, “Death is Hard Work”, takes place during the civil war. Abdel Latif, a leader of the opposition forces, dies in a Damascus hospital. He makes his son, Bolbol, promise to bury him in his native village of Anabiya, near Aleppo. Bolbol takes his father’s body in a minivan and convinces his sister Fatima and brother Hussein to accompany him on the journey.

The journey is a slow one, taking in the multiple checkpoints set up by the various factions – governmental and then Islamist – that successively control the territories along the way. Khaled Kalifa’s narrative blends despair and humor, as siblings are torn apart and then reconciled, memories of love return and the father’s body decomposes on this never-ending funeral journey.

As much as “Death is Hard Work” can be read as an allegory of the interminable Syrian civil war, “No One Prayed Over Their Graves” appears first as a celebration of the Syria of yesteryear. The book begins at the end of the 19th century, when Aleppo is still under Ottoman rule. Hanna, a Christian, and Zakaria, a Muslim, have been friends since childhood, when the latter’s parents took in the former, whose family had been massacred. Both come from well-to-do backgrounds: they spend their youth in pleasure, traveling as far as Venice and having a Jewish architect friend build a “citadel” in Aleppo to house the most beautiful courtesans.

This life of debauchery and recklessness, uninterrupted by their respective marriages, comes to an abrupt halt when a flood ravages their village outside Aleppo, bringing death and desolation to their families. This novel takes us on a journey through Syria’s history, from the fall of the Ottoman Empire to the birth of the Syrian Republic, via the arrival of survivors of the Armenian genocide and the French occupation. Marked by tragedy, Hanna and Zakaria maintain their friendship, against all odds, while the world around them crumbles.

The town on the outskirts of Aleppo to which Hanna and Zakaria return after the tragedy is also called Anabiya. The same fictitious name as the village where Bolbol has promised to bury his father. Khaled Khalifa was also born near Aleppo. Despite censorship, torture (arrested during a demonstration in 2012, he emerged from prison with a broken hand) and the war, he never left Syria. He died of a heart attack in Damascus in September 2023.