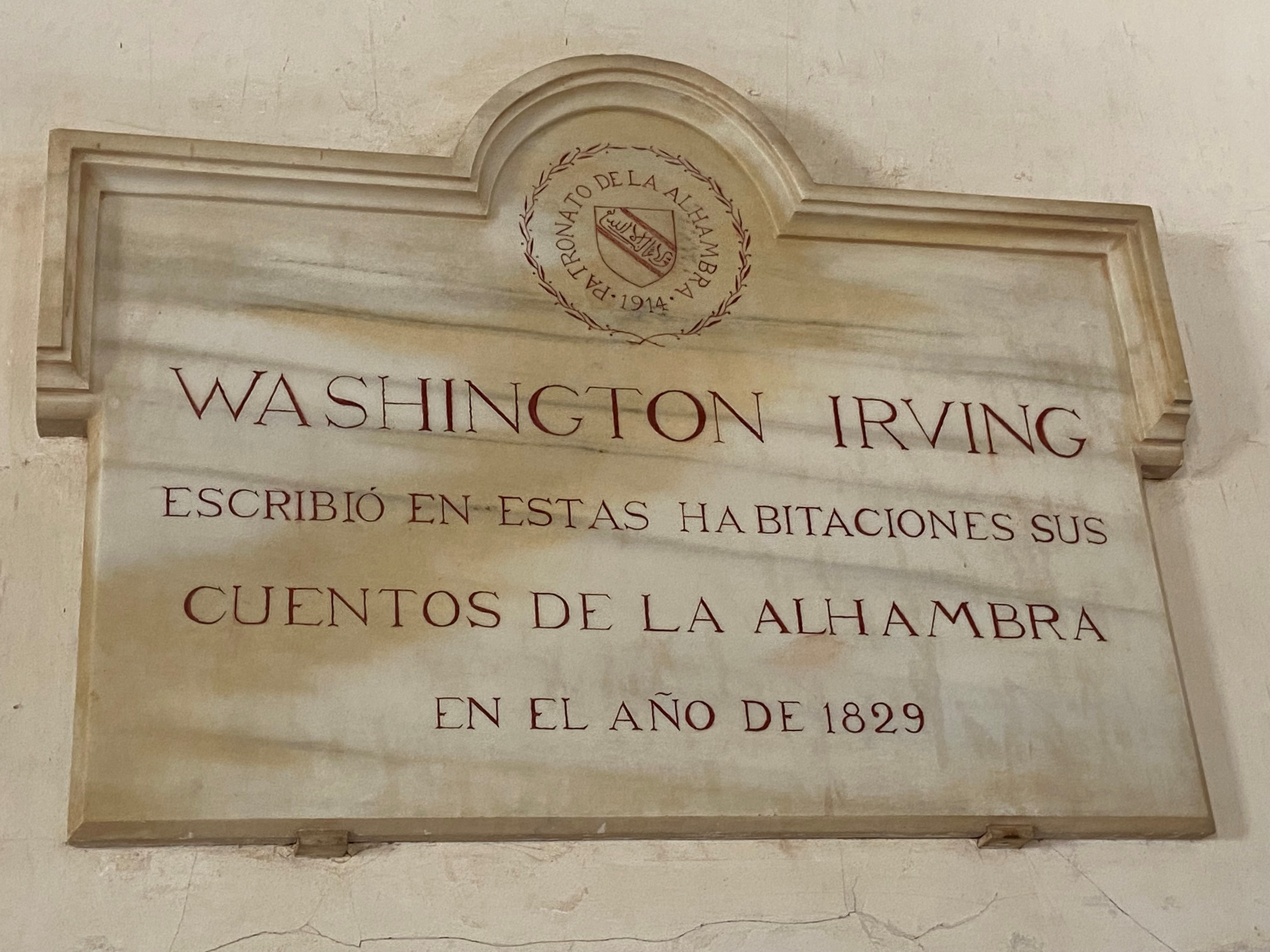

Last summer, Céline and I traveled for one week in Andalusia. I was looking for a few good books. I could have read « Tales of the Alhambra » written by the American author Washington Irving during his stay in 1829 in the Moorish fortress. The book is said to have revitalized the interest for this iconic monument in Grenada and for the Islamic past of « Al-Andalus ». I could also have re-read « For Whom the Bell Tolls » by Ernest Hemingway, in particular chapter 10 when we were visiting the city of Ronda and were looking down the canyon of the Tajo. Even if most of the novel is set in Madrid’s region and even if Hemingway said that he fabricated the story entirely, the critics agree that the famous scene where Nationalists are thrown from the cliffs by the Republicans is inspired by real events in Ronda, in early 1936, at the beginning of the Spanish Civil War.

But during our Andalusian week, it is two verses from two poems by French poet Louis Aragon, sung by Jean Ferrat who were constantly in my head and encouraged me to discover the works of Antonio Machado and Federico Garcia Lorca, two giants of Spanish literature, both born in Andalusia and both dead during the Spanish Civil War era.

In « Les Poètes (The Poets) », Aragon writes:

« Je ne sais ce qui me possède

Et me pousse à dire à voix haute

Ni pour la pitié, ni pour l’aide

Ni comme on avouerait ses fautes

Ce qui m’habite et qui m’obsède

Celui qui chante, se torture

Quels cris en moi, quel animal

Je tue ou quelle créature

Au nom du bien au nom du mal ?

Seuls le savent ceux qui se turent

Machado dort à Collioure

Trois pas suffirent hors d’Espagne

Que le ciel pour lui se fît lourd

Il s’assit dans cette campagne

Et ferma les yeux pour toujours (…) »

« I do not know what possesses me

And pushes me to speak aloud

Seeking neither pity nor help

Nor to make a confession

Just for that which dwells within me and haunts me

He who sings tortures himself

What cries within me, what animal

do I kill, or what creature

In the name of good or evil?

The only ones who knew were silent

Machado is sleeping in Collioure

Three footsteps outside Spain

Were enough for the sky to become heavy for him

He sat in this countryside

And closed his eyes forever (…) »

In this last verse, Aragon evokes Machado’s exile after the fall of the Republic, which he supported while his brother was in the Nationalist camp. He flew to France with his mother and stopped, exhausted, in Collioure a few kilometers from the Spanish border. He died in his hotel room on February 22, 1939, three days before his mother.

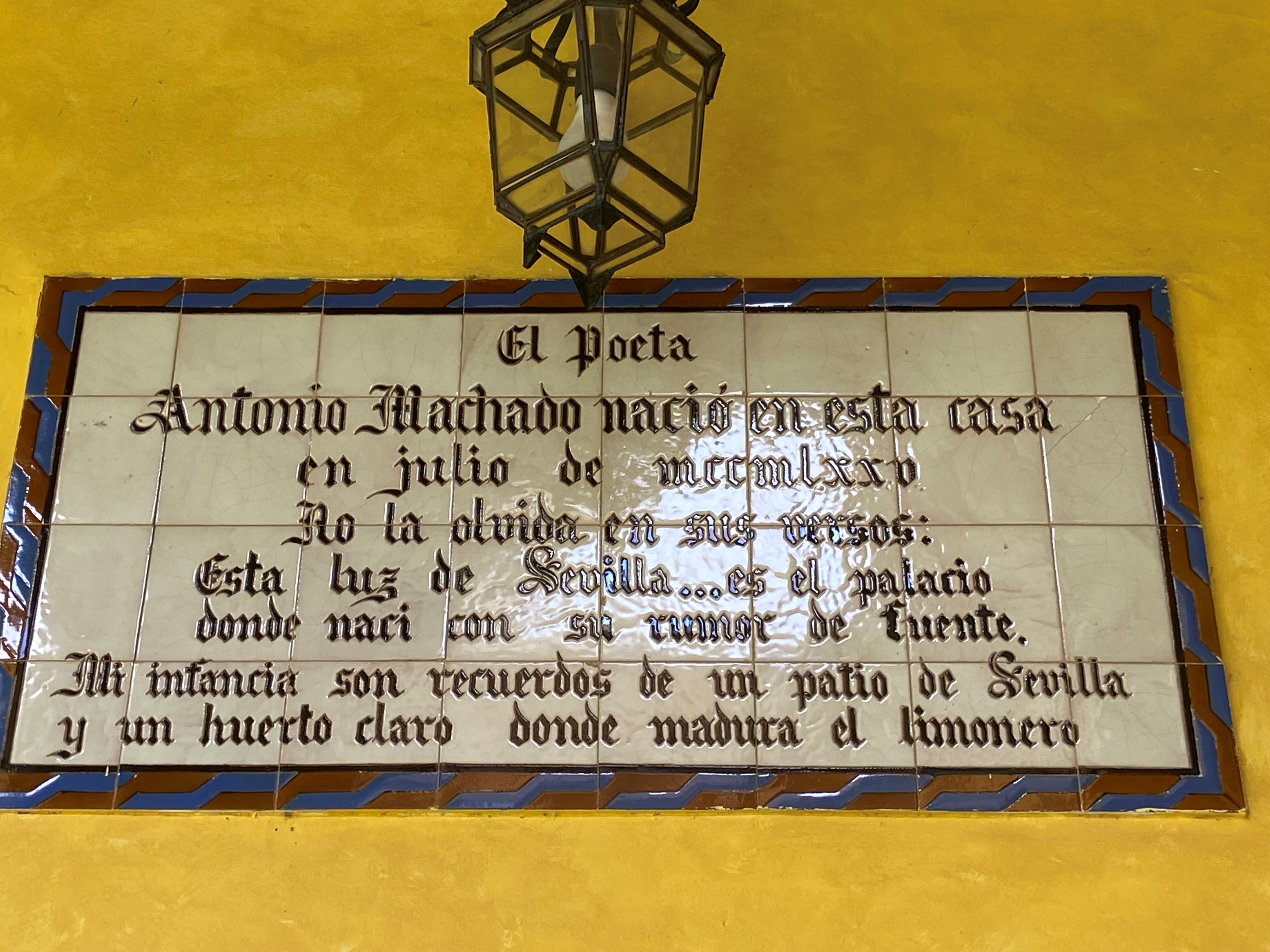

If he died in Collioure, it is in Sevilla that Machado was born in 1875 in the Palace of las Duenas, the superb residence of the Dukes of Alba in the Andalusian capital. We visited this house with its front covered by bougainvillea and its elegant patios. In one corner stands a plaque with the poet’s words remembering his childhood, the Sevillian light, the fountains’ rumor and the odor of the lemon trees. Machado was not a descendant of the Dukes of Alba. His father rented one of the outbuildings to lodge his family.

He was a modest French teacher who taught in Soria, Segovia but also in Baeza, a superb baroque city in Andalusia, away from the classic itineraries. A statue of the poet, sitting on a bench with a book open on his knees is a testimony to his stay in the city, in which he arrived desperate, just after the death of his wife Leonor, victim of tuberculosis.

One of Machado most famous poem is « Se hace camino al andar (The Path is made by walking ») put in music by Joan Manuel Serrat:

« Caminante, son tus huellas

el camino, y nada mas ;

caminante, no hay camino,

se hace camino al andar.

Al andar se hace camino,

y al volver la vista atras

se ve la senda que nunca

se ha de volver a pisar.

Caminante, no hay camino,

sino estelas en la mar. (…)»

Walker, your footprints

are the road and nothing else;

walker, there is no path,

the path is made by walking.

When you walk, you make a path,

and when you look back

you see the path that will never

Be stepped on again.

Walker, there is no path,

But wakes in the sea (…) »

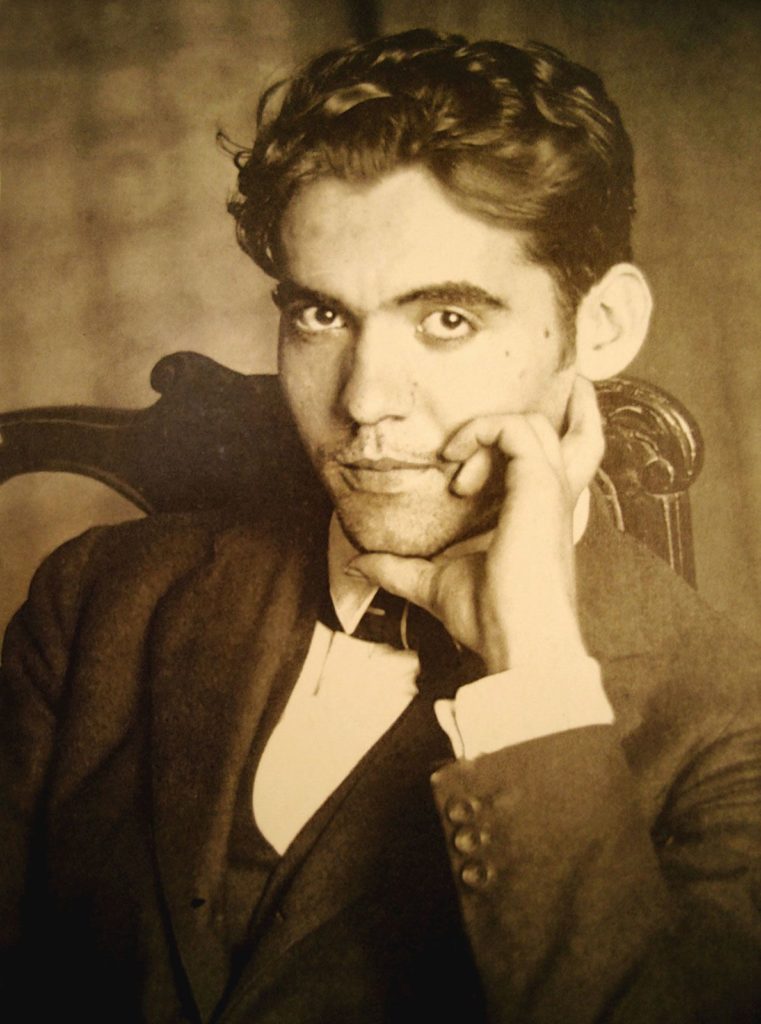

The second poem by Aragon sung by Ferrat, « Un jour, un jour (One Day, One Day)» recalls Federico Garcia Lorca and his execution in 1936 by a group of Phalangists in a small village outside Granada.

« Tout ce que l’homme fut de grand et de sublime

Sa protestation ses chants et ses hérosAu-dessus de ce corps et contre ses bourreaux

A Grenade aujourd’hui surgit devant le crime

Et cette bouche absente et Lorca qui s’est tu

Emplissant tout à coup l’univers de silence

Contre les violents tourne la violence

Dieu le fracas que fait un poète qu’on tue

Un jour pourtant, un jour viendra couleur d’orange

Un jour de palme, un jour de feuillages au front

Un jour d’épaule nue où les gens s’aimeront

Un jour comme un oiseau sur la plus haute branche (…) »“All that man was great and sublime

His protest, his songs and his heroes

Above this body and against its executioners

In Granada today arises before the crime

And this absent mouth and Lorca who is silent

Suddenly filling the universe with silence

Against the violent turns violence

God the crash made by a poet who is killed

One day, however, one day will come the color of orange

A palm day, a foliage day on the forehead

A bare shoulder day when people will love each other

A day like a bird on the highest branch ».

Garcia Lorca was born in 1898 in Fuente Vaqueros a few kilometers from Granada. His father was a rich farmer and trader in the sugar industry. At eleven, the family moved to Granada but kept its rural roots.

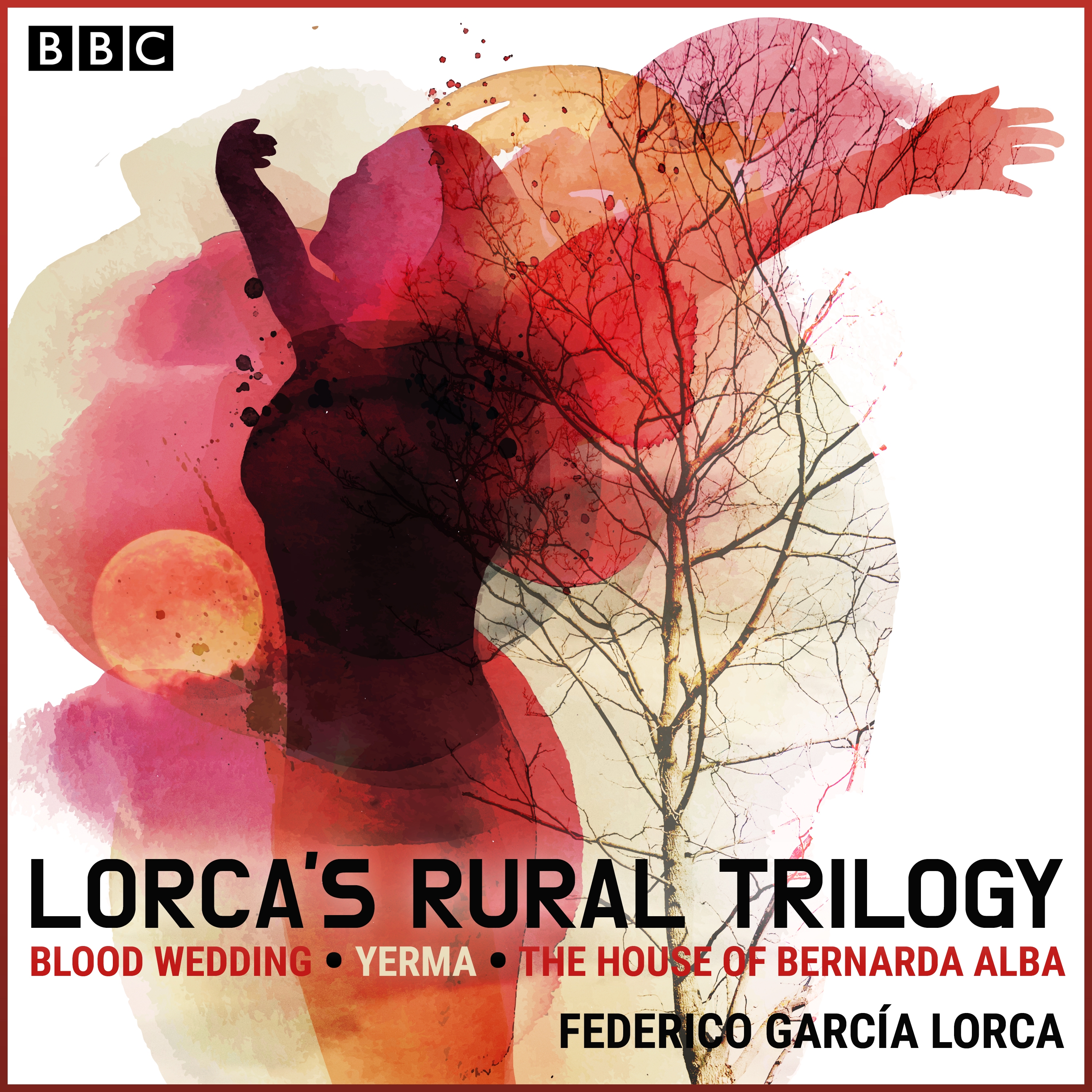

His knowledge of the countryside in Andalusia, of its sometimes archaic traditions and his acute conscience of the social disparities in the villages have inspired his theater work. I read three plays which he wrote and directed when he led « La Barraca », a student itinerant troupe which had the mission to bring theater to rural Spain: « Blood Wedding (Bodas de Sangre), « Yerma » and « The House of Bernarda Alba (La Casa de Bernarda Alba) ». The three plays illustrate the danger for women to love according to their heart in a setting in which social norms, their good name and « honor » have more value than their feelings and freedom. I read these three works with great pleasure and would very much like to see them played in Spanish or in translation.

Garcia Lorca is also famous, and rightly so, for his poetry. I was for example very surprised to learn that Leonard Cohen’s superb song « Take this Walz » was translated and adapted from his poem « Little Viennese Walz ». The Canadian singer was a big admirer of the Andalusian poet – he called his daughter « Lorca » – and admitted having taken about 150 hours to translate into English « Pequeño vals Vienés ».

Garcia Lorca’s political positions, his homosexuality, made him a symbolic target for the Phalangist groups who were creating havoc in Granada. The details of his arrest and his death remain vague. His remains were never found. But his execution inspired Machado to write one his most famous poems « El crimen fue en Granada (The Crime was in Granada) ».

« The crime

He was seen walking between rifles,

down a long street

and out into the cold countryside,

under a few dawn stars.

They murdered Federico

when the sun rose.

The firing squad

didn’t dare to look him in the face.

They all closed their eyes;

they prayed: not even God saves you!

Federico fell dead,

with blood on his brow and lead in his guts?

… you know the crime was in Granada,

poor Granada!? In his Granada. »