I believe there are two ways, more complementary than contradictory, to be seduced or moved by a painting. Either it is the composition, the perfection of the drawing or the colors. Or, probably also thanks to the artist’s technique, it is the story and the lives of the characters represented which are more directly the source of the attraction. During my last two trips in Italy, I very much enjoyed contemplating two frescoes which, several centuries later, inspired an author to write a book which I had read before seeing the paintings.

If I love going around museums looking for attractive paintings, I even prefer frescoes. Nothing matches the experience of admiring a painter’s talent in the location where his work was done and for which it was designed. Italy is of course a paradise for anyone who loves affresco art. From my travels, I keep wonderful memories of « The Last Supper » by Leonardo da Vinci in Milan, the Sistine Chapel by Michelangelo in the Vatican, the cycle of “The History of the True Cross” by Pierro della Francesca in Arezzo or Giotto’s frescoes in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padova or the Saint Francis Basilica in Assisi.

« Allegory of Good and Bad Government », Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Palazzo Publico, Siena

This summer, despite the COVID-19 pandemic, I managed to go for a week in Tuscany. Florence’s streets and the Piazza del Campo in Siena were busy, but free of overwhelming tourist crowds. In order to visit the museums, we needed to book in advance a time slot with a limited number of entries available. This required some organizing, but it was worth it. We did for example go around San Marco’s Convent in Florence and marvel at Fra Angelico’s frescoes in a surprising quietness. That calm, and the masterpieces decorating each cell, almost gave me the urge to become a monk – at least for one week.

In Siena, we discovered in the same tranquility the frescoes of the « Allegory of Good and Bad Government » painted by Ambrogio Lorenzetti in the 14th century in the Palazzo Publico, ordered by the Council of Nine, the elected magistrates who managed the city. Those frescoes are among the works of Sienese art described and reproduced in the short but exquisite book « A Month in Siena » by Hisham Matar. The writer, who since a visit to the National Gallery in London when he was 19 has a strong predilection for the Sienese school of painting, retires to the Tuscan city after the publication of his book “The Return” describing his search for his father, a Libyan opponent who disappeared in Qadhafi’s jails. He spends hours in the rooms of museums and palazzi and walking the steep streets of the medieval city. One of the chapters describes how he explored with his wife the allegories of Wisdom, Justice and Concorde and the consequences that good and bad government can have on cities and countryside alike. He underscores that these paintings are among the first in art history to be secular, and adamantly so.

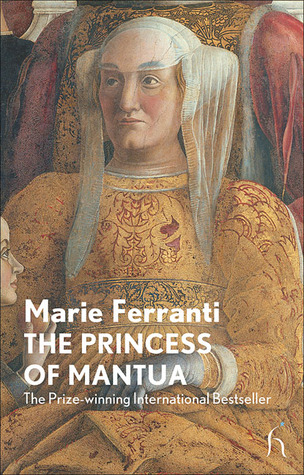

Hisham Matar’s book reads like a collection of reflections and sometimes digressions as the author admires frescoes and other paintings in Siena. In « The Princess of Mantua (La Princesse de Mantoue)», French author Marie Ferranti proposes an even more radical experience for an encounter between art and literature. The spark that inspired her novel is Andrea Mantegna’s fresco in the « The House of Spouses» in the San Giorgio castle in Mantua. I visited the palatial house of the Dukes of Gonzaga last year and was struck by the expressivity of the faces in the family compositions painted by Mantegna. So much that, like the author, I found myself imagining the lives of these aristocrats during the Quattrocento in Lombardy.

Marie Ferranti focuses on Barbara von Brandenburg’s face, « with her eyes tired and yellow, stretched towards the temples like a cat». Through letters exchanged with her cousin Maria von Hohenzollern, an imaginary correspondence but build on a patient documentation work, the novelist tells the story of this young German princess who was sent at age 10 on the other side of the Alps to marry Ludovico, the heir of the Gonzaga, then himself still a puny teenager. When her husband comes back from several years fighting in wars, he has gained in confidence, as much in conducting the Duchy’s affairs as in bed where he molests his wife. Births follow each other: Barbara manages to fit in the mold of a mother, spouse and adviser, but will never find it in herself to love Paola, her youngest daughter, born a hunchback. She becomes bitter, retreats and shuts herself in the « House of the Spouses », the jewel case completed by Mantegna which was designed to showcase to the world the power of the Gonzaga couple.