My economics history professor was telling us about settlers “in the Chesapeake Bay”. I had just arrived from Europe, was studying in Chicago and had no idea what place he was talking about. I had to look it up in an atlas or a dictionary.

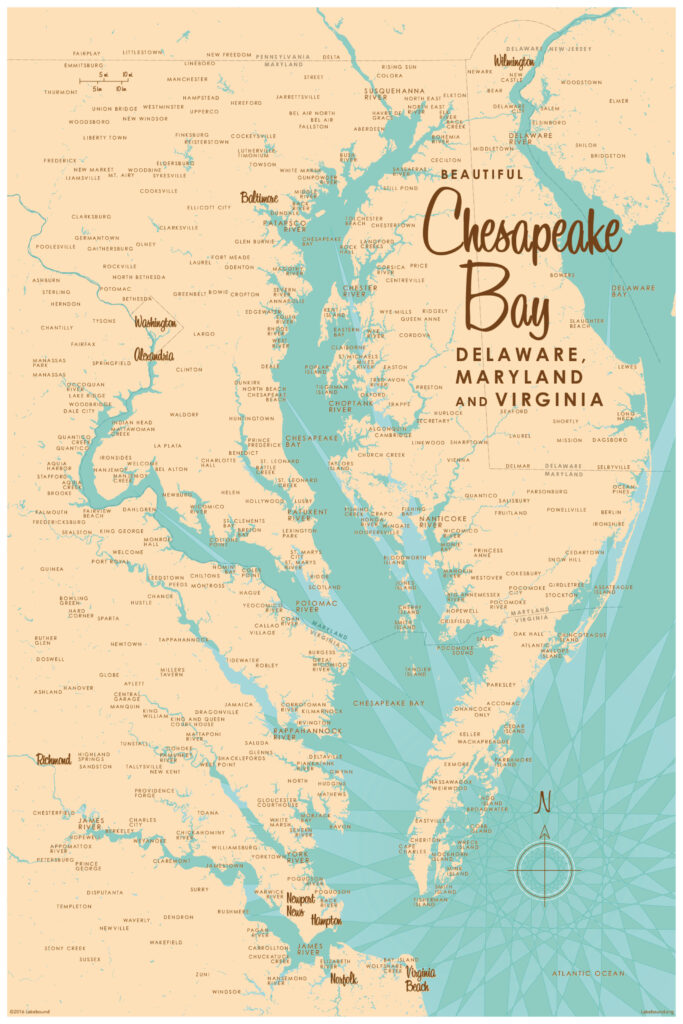

Since then, having settled in the Washington, D.C. area over twenty years ago, I’ve become much more familiar with the Chesapeake Bay, that gigantic estuary that seems to go inland south of Virginia and runs up between Virginia and Maryland to beyond the port of Baltimore. At nearly 320 kilometers long, it’s the largest estuary in the United States. I’ve kayaked here and discovered, with the help of friends, the pleasures of sailing. I remember sailing towards the Thomas Point lighthouse off Annapolis as well as the calm, almost hidden coves where we’d anchor for lunch between the foliage of trees. Thanks to friends who often invite us, we also spend many weekends in a charming old farmhouse at the end of the Patuxent River. From the porch, with a drink in hand, we enjoy their hospitality and the sumptuous sunsets that this region, little known abroad, has to offer.

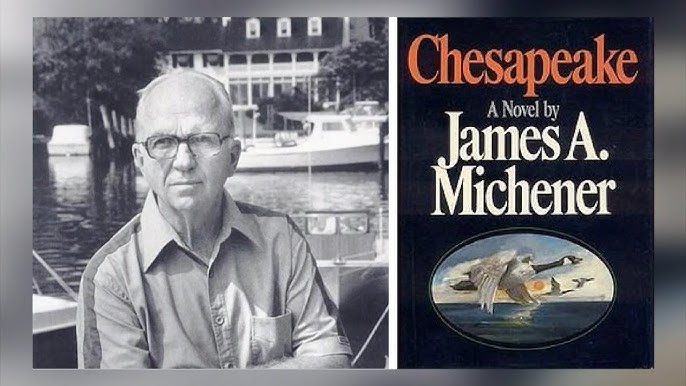

In our friends’ home is a copy of the novel “Chesapeake” by American writer James A. Michener. A real doorstopper of more than 800 pages, it intrigued me. But it wasn’t until, a few months ago, I passed through Doylestown, a charming Pennsylvania town, that I decided to pick it up. Michener was born in this town, and it was by chance that we visited the lovely little art museum that bears his name. One room is dedicated to his life and work as a writer.

Michener’s method is to illustrate a region and its history through a series of long family stories that interweave over the centuries. His novels are based on detailed research. To write “Chesapeake”, the writer settled in St. Michaels, a small port on Maryland’s Eastern Shore.

The novel begins in 1583, when Pentaquod, an Iroquois Indian, travels down the Susquehanna River to settle on the banks of the Choptank, a small river bordered by swamps on the Eastern Shore. Mitchener builds a world around the fictional town of Patamoke. Settlers arrive from Europe, and despite some initial respectful contact, the Indian tribes soon disappear from the scene. The Europeans bring with them their religious quarrels. The Steeds were English Catholics who found refuge in Maryland, a colony granted to Catholics by the English crown. Thanks to the tobacco trade and cultivation, they soon became wealthy landowners. There they rubbed shoulders with the Paxmores, a family of Quakers who had fled Puritan persecution in Massachusetts and specialized in shipbuilding. The Turlock family lives in the marshes. They hunt geese and gather oysters. They are those “White Trash” living close to poverty but who always somehow manage to get by.

These family destinies are interwoven with history. The Steeds oscillated between loyalty to England and the American independence movement, before siding with freedom and fighting alongside George Washington. But they recruited black slaves to grow the tobacco that made them rich and clung to slavery when the Civil War broke out. The Turlock family are excellent sailors. One of them became a privateer and broke the English blockade that closed the Chesapeake, while another captained a slave ship. Soon the Cater family appears, Blacks whose ancestors were taken from Angola. They will experience slavery in the tobacco fields, before being promoted to the Steeds’ domestic service, being emancipated and finally becoming involved in the civil rights struggle. The Paxmores, in their Quaker rigidity – Michener was adopted by a Quaker family – form the moral pole of this community. Pacifists, they didn’t get involved in the wars, but they were one of the Maryland relays of the Underground Railroad, the clandestine network that enabled Southern slaves to escape to the North. Yet the last of the Paxmores was working in the White House when the Watergate scandal broke. He covers up for Nixon and his cronies and must serve out his sentence in a federal penitentiary.

This wide-ranging historical and family saga ends in 1978. It gave me a better understanding and appreciation of this region, which is close to the capital of the United States and yet sometimes seems so far away, as if turned towards its rivers, boats and marshes. A world where you fall asleep lulled by the waves, and where the geese wake you up in the morning. We step onto the pontoon to lift oyster cages under the watchful eye of a pair of ospreys. Later, we feast on fresh oysters, opened with a knife, or, in season, crabs whose shells we smash with a mallet. As the sun sets, it’s been a good day.