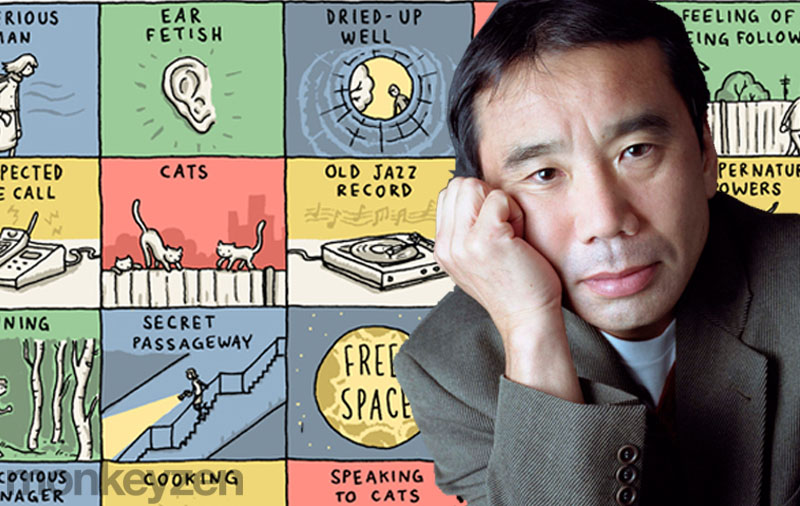

I was hesitant for a while before writing a post about Japan, mainly because I only spent three days there for a conference in Tokyo. But I have excellent memories and it is in Tokyo that I had one of my best dining experience. I have finally decided to take the leap by talking about three novels by Haruki Murakami, the star of Japanese literature and three by Amélie Nothomb, the francophone writer who nowadays is probably closest to Japan. Murakami and Nothomb have several elements in common. Both spent part of their childhood in the Kobe region. Both are prolific writers and the launch of each of their new opus is – all proportions being kept in mind – a media event. Some differences, however. Murakami, for example, is a very secretive author who refuses radio and TV interviews, while Nothomb is not averse to the spotlights, happy to be interviewed wearing one of her signature black hats. I like the idea of contrasting Amélie Nothomb’s European vision of her favorite country with Murakami’s, who is often presented as the most western of Japanese authors.

Indeed, Haruki Murakami’s works are full of references to Western culture, for example classical music and jazz. He explained that when he found it difficult to write his first novel, he composed the opening pages in English and then translated them to Japanese and that it is how he found his “voice”. The first novel I read from him is the imposing « IQ84 », 932 pages which I turned with joy. A young woman, Aomame, has taken a taxi to go to an important appointment, but she ends up stuck in a Tokyo traffic jam on a suspended highway. The cab’s radio is playing Janáček’s “Sinfonietta”. The driver suggests that she could take one of the emergency pullouts which opens on staircases that could bring her back at street level, but warns her when she decides to use this escape route, « please remember, things are not what they seem ». The novel creates a universe where daily life suddenly gives way to a different, magic world, but the movement between reality and the surreal universe flows naturally, like opening a door. In parallel, the book also tells the story of Tengo’s life. He is an unpublished writer and a mathematics teacher who is dragged somewhat against his will in a literary hoax when he accepts to rewrite a promising manuscript whose author wants to remain hidden. The novel ends when Aomame and Tengo meet, or rather meet again, as they remember that, as children, they were classmates and that one day they held each other tightly by the hand, without a word, when all the other students had left the classroom.

In « Tokyo Fiancée (Ni d’Eve ni d’Adam) », Amélie Nothomb, for once, writes about love. She is back to Japan as a young adult, but has forgotten the Japanese that she had learned during the blessed years of her childhood. She thinks that working as a French tutor is the best way to get to practice the language. Rinri, an eccentric Japanese, is her first student. The book starts with funny moments of incomprehension. But while Amélie reunites with her childhood tastes, she also let herself being seduced by Rinri who leads her through all the obligatory steps of dating Japanese style, including climbing up the slopes of Mount Fuji. The adventure, despite its charm and vigor, becomes a misunderstanding: Rinri is deeply in love and dreams of marriage, while, inverting the roles, Amélie is happy to have a try with koi, a type of sexual relationship based on camaraderie and which explicitly avoids romantic effusions. In the end, unable to say no to Rinri’s proposal, she finds no other solution than to take a one-way ticket to Belgium and escape. She however keeps a very soft spot for the months she shared with Rinri.

While she discovers the charms of a Japanese love story by night or during the week-ends, Amelie, by day, gets her initiation in another key feature of life in Japan: working for a big Japanese corporation, the prestigious Yumimoto. Full of enthusiasm and despite trying her best, the young Belgian makes successive blunders. As a result, many in her chain of command lose face. She even manages to antagonize her direct boss, Miss Fubuki Mori, whom she nevertheless admires for her stupendous beauty. Going down the corporate ladder, Amélie ends up in charge of bathroom maintenance. She becomes a victim of the Japanese corporate machine which doesn’t fire underperforming employees, but ostracizes them, so that, after too many humiliations, they end up resigning. This descent into hell is told in “Fear and Trembling (Stupeur et Tremblements)” with the brilliant and self-deprecating style which is Amélie Nothomb’s signature. This novel has sometimes been seen as a caricature of life in a Japanese company. I believe Amélie Nothomb’s self-deprecating humor allows her to avoid that pitfall since it is above all her own failure that she describes. In any case, I recommend reading “Fear and Trembling” together with “Tokyo Fiancée” as I just did. Both novels cover the same stay by Amélie Nothomb in Japan, coming out of college, as a pilgrimage to the wonderful country of her childhood. On the one hand, her failed attempt in a Japanese company. On the other hand, a love story which even if surprising in its ending, shows the tenderness and passion Amélie has for Japan.

In « Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage», Haruki Murakami invites us to revisit the troubled years of adolescence. Tsukuru Tazaki is an engineer who is single and whose life is devoted to the design of railway stations. Sara, his new girlfriend encourages him to get to the bottom of a trauma dating from his teenage years, which he would like to suppress but is still haunting him. In his high school in Nagoya, he was part of a group of inseparable friends with two other boys and two girls. Each of the friends, except for him, had a name evoking a color: « Red », « Blue », « White » and « Black ». One day, suddenly, he was excluded from the group without any explanation. Nobody wanted to talk to him anymore. Since then, he has been carrying with him a feeling of emptiness. Twenty years later, he goes looking for his past and learns in meeting his former friends “Blue” and “Red” that the reason for his ostracism was that “White” accused him of raping her. Tsukuru then flies to Finland where « Black » lives with her Finnish husband and lives as a potter. She informs her that the friends had realized that the accusation was fake: “White” had indeed been raped, but not by him. The group decided not to contradict her because she was mentally instable and they estimated that Tsukuru was solid enough to withstand his exclusion. At the end of the novel, written in a more realist vein than other books by Murakami, but always with an impressive fluidity, Tsukuru gets back to Japan appeased, and hopes to reconnect with Sara.

After Murakami’s pilgrimage back to adolescence, it is towards early childhood that Amélie Nothomb’s novel « The Character of Rain (Métaphysique des Tubes) » leads us. The third child of the Belgian Consul, Amélie was born in Kobe. She spends the first two years of her life as a vegetative tube without any clear idea of herself. But then her grand-mother gives her a piece of white chocolate that she brought back from Belgium and the miracle happens: she awakes to consciousness. She discovers an enchanting world made of Zen gardens, a father who learns to sing Noh theatre, and a wonderful nanny, Nishio-san, who teaches her Japanese. She admires the mountains, the rain, the sea and almost drowns twice. She however develops a fear and horror for the birthday gift received from her parents: three koi in the garden’s pond. The book is a surprising but fascinating recreation of those early years which we do not remember even though they have such a strong influence on us. Amélie Nothomb’ s sparkling humor is always present, but it also includes pages rich in emotion, for example those describing Kobe’s bombing in 1945, from which Nishio-san, then a young girl, was her family’s only survivor.

Amélie Nothomb Une Vie entre deux Eaux by welcomtou

I finish this overview with « The Wind-Up Bird Chronicles» by Haruki Murakami. It is again a story where the daily routine – the grey life of Toru Okada, an unemployed man whose wife Kumiko tasked of finding back their disappeared cat – gets suddenly mixed with the bizarre and the surreal. A fortune-teller is hired to find the cat, Toru’s wife disappears without any explanation, he goes hiding at the bottom of a dried-up well from which he emerges with a strange blue spot on the cheek, a former lieutenant from the Japanese Imperial Army tells him about the horrors he experienced in Mandchoukouo, the state installed by the Japanese in Manchuria during World War II. This all seems initially confusing and as often with Murakami one never knows what to expect after opening the door. But this is part of the fun and in the end, we end up back on our feet in awe of his gift for juggling reality together with dreams.